Narayan Vaman Tilak (1868-1919): A Christo-Centric Move beyond the Church and Christianity

When Ramabai published the first collection of Christian bhajans she included a few of her own publications but relied mainly on the work of Narayan Vaman Tilak. Tilak grew up under the influence of the Marathi bhakti saints, known to the world through a series of translations by missionaries called The Poet-Saints of Maharashtra.1

Tilak turned to Christ in 1895 after a period of disillusionment with Hinduism during which he contemplated beginning a new religion. He met a missionary on a train journey who first spoke at length with him about Sanskrit poetry and later urged him to read the New Testament. The reaction to Tilak’s baptism was electric, and he was separated from his wife for over four years before she rejoined him and also later came to Christ.

Like many Hindus who turn to Christ, Tilak assumed that Christ and Western Christianity are part of one package, and he became a good Christian. But a major transition began in his life one day when he heard the pilgrims of the Marathi poet-saints singing their songs and decided to write bhajans to Christ. As his pilgrimage progressed Tilak became a remarkable pioneer in what we now call contextualization, developing patterns of evangelism and discipleship that fit local contexts.

Tilak and his wife had visited Ramabai at Mukti in 1905, just a few months before the revival broke out there. But there were too many differences between them for close cooperation to develop. In fact, it was at Mukti that Tilak’s wife Lakshmibai, by then following Christ for five years, was convinced by Ramabai to cease wearing the bindi (red dot on the forehead). Lakshmibai reflected on this in a presentation given in 1933:

After becoming a Christian, for many years I would apply kunku. No missionary objected to this. Once, however, a learned Indian Christian lady connected kunku with the Shakta cult, misled me, and took a promise from me that I would never again apply kunku. Afterwards Tilak explained to me the meaning of kunku. But since I had given a promise I did not apply it again and Tilak never insisted that I do so.2

But Tilak went far beyond some outward accommodation to Hindu forms. The themes of his writing also resonated with bhakti, while being faithful to biblical revelation. In 1917 his life took another turn, this time through meeting a Hindu during a train journey. This Hindu man referred to the dynamism of Tilak as a young leader, and asked what had happened to him.

Tilak realized he had drifted too far from his own people, and was now isolated in communalized Christianity. After months of struggle and hesitation he resolved to begin a new movement which he called devachadarbar, God’s royal court. This was to be a brotherhood of the baptized (Christian) and unbaptized (Hindu) disciples of Jesus; what today we might call a true church that transcended the sociological boundaries of religious affiliation.

Tilak’s new work did not proceed far, as he died within two years of its start. But he left a legacy and a dream that remains to be realized by new generations of Hindus who follow Jesus.

Endnotes

1. 12 volumes published between 1926 and 1941, many available in reprint still today.

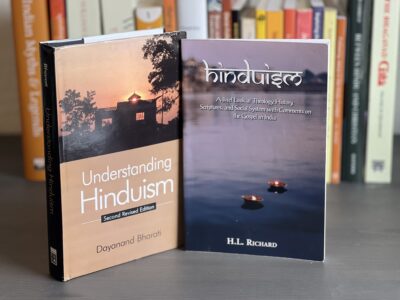

2. The Marathi original of this is in Tilak, Lakshmibai, Sampurna Smrutichitre, ed. Ashok Devdatt Tilak, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, 1989, pg. 704. For the English translation see Richard, H. L., Following Jesus in the Hindu Context: The Intriguing Implications of N. V. Tilak’ Life and Thought, Pasadena: William Carey Library, 1998, pg. 118.

Note: These biographies originally appeared in the chapter “The Church and Hindu Heritage: Historical Case Studies in a Rocky Relationship” in Rethinking Hindu Ministry, Pasadena: William Carey Library, 2011.

[…] history.3 Two of the earliest Christian bhajan writers were Purushottam Choudhary (1803-1890)4 and Narayan Vaman Tilak (1861-1919).5 For Choudhary and Tilak, bhajans were their natural form of expressing worship. Their […]